In testimony to the House Foreign Affairs Committee in May 2023, Assistant Secretary of State Jessica Lewis stated that “[AUKUS] Pillar II may have arrived just in time,” referring to a generally accepted assessment that China is ahead of the United States and its allies in 19 of 23 technologies relevant to AUKUS Pillar II. While advancing the state of the art in all of Pillar II technologies is an important goal in addressing this gap, we can immediately shift the balance in those areas contributing to subsurface and seabed warfare (SSW) through existing and proven capabilities. Collectively, the AUKUS participants can address this technological imbalance and do so at pace by leveraging commercially available vehicles, sensors, and payloads to get relevant capability into SSW warfighters’ hands.

To achieve this very near-term solution, the United States needs a comprehensive approach to navigate opportunities, overcome challenges, and reshape existing legislative frameworks to implement Pillar II.

Quantity Has a Quality All Its Own

Rightfully, the main buzz around AUKUS centers on Pillar I and the pathway to an indigenous Australian nuclear submarine. The breadth and scope of that endeavor—rolling up 75 years of the nuclear submarine ecosystem from two sovereign nations to create a brand new one in a third independent nation—is epic and without true precedent. In the case of nuclear-powered submarines, quality establishes its own quantity.

Pillar II headlines and discussions have focused on the advancement of relevant undersea technologies to push the state of the art in SSW through collaboration and mutual development of new capabilities. Implementing undeveloped, or newly developed technology and fielding at scale in useful numbers for warfighters still takes years in the US, acquisition reforms and alternative contracting methods notwithstanding. Moving up the technology readiness level (TRL) ladder is risky, time phased, and expensive.

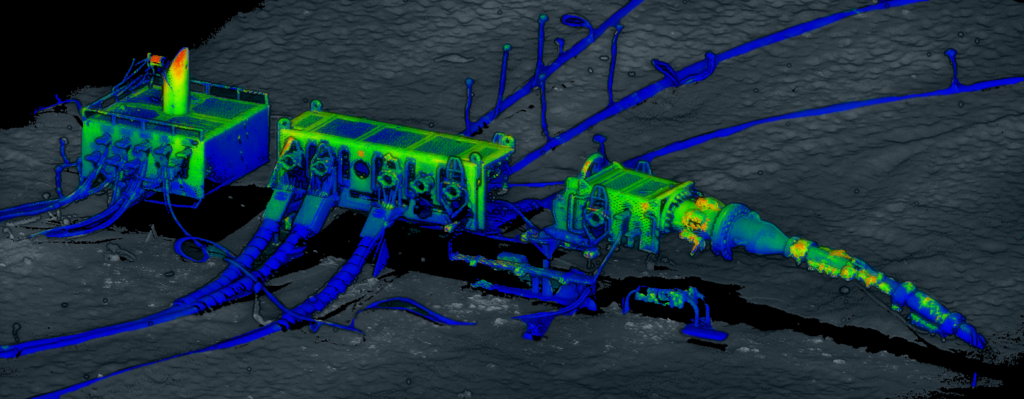

However, in the SSW fight, small, uncrewed, autonomous vehicles, perhaps even those that are expendable or attritable, carrying a variety of sensors, and seafloor networks serving a variety of functions are available right now. Sensor systems with limited range or function deployed in significant numbers—quantity—offer meaningful options for a theater commander—a desirable quality, to be sure.

The near-term solution is to rapidly and widely implement existing commercially available technologies regardless of AUKUS nation of origin. Closing the perceived technology gap, referenced above, that was ceded over years will take years to win back. The Replicator initiative tacitly acknowledges the challenge of regaining the technology edge through its approach to rapidly deploy legions of autonomous platforms within just a couple years.

Raising the Pillar, Lowering the Flag

Commercially available technology, in use by companies in conducting energy, communications, and ocean survey operations, and by ocean science and research institutes, is highly capable and available now to support SSW mission sets. Integrating sensors and payloads into existing vehicles for military rather than commercial operations is a low risk and quick way to address Pillar II goals. Facilitating this across national AUKUS boundaries, at least in the US, requires action from Congress, the Department of State (DoS), and the Department of Defense (DoD).

Three areas present hurdles: legislative action; modification of export controls through International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR); and management of Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI).

Legislative Action

To date, only two bills referencing AUKUS have become law and both are National Defense Authorization Acts. Several bills are in early stages in either house of congress addressing various legislative changes or authorization. No DoS authorization act has been passed in recent years and none appropriating money for AUKUS activities. Without legislation or authorization, DoS cannot make changes to ITAR rules opening the door for accelerated movement of technical information and material within the AUKUS group. Stalled initiatives, such as the Senate’s Truncating Onerous Regulations for Partners and Enhancing Deterrence Operations (TORPEDO) Act of 2023 directly address the issues and should be enacted into law directly.

Adapting Export Controls

Long-standing exemptions for Canada covering technical data transfer and enumerated items on the US Munitions List (USML) allow the free flow of Pillar II technologies. DoS can adopt this same approach with our other most trusted partners. The same language and principles can be rapidly incorporated into our ITAR. “Pre-licensing” by carving out specified exemptions in the USML will quickly allow for seamless collaboration between government, research, and commercial entities under the AUKUS umbrella. Proposed legislation in both the House and the Senate leans into DoS to make these changes.

“Controlled AUKUS” Information Category

Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) evolved from several threads of unclassified but sensitive, often export controlled, technical and other information. Both the DoD and DoS acknowledge this is a significant hurdle. Overclassification was characterized in 2023 by the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs as “unbelievably ridiculous” and this extends to overly controlling CUI. Further, improper markings and categorization throw sand in the gears. CUI is codified in DoD instruction but application is inconsistent and confusing and stymies what should otherwise be a smooth authorization process. Others have already suggested creating a special category to pre-clear the transfer of information within AUKUS channels. Creation of such a handling caveat may be effective in both the UK and Australia as each have their own processes for determining what is and what is not sensitive and what can be readily shared. A trilateral handling caveat could cut across the unique systems in place without having to reconcile the rules of each country.

Conclusion

Pillar II is moving forward within the current AUKUS ecosystem but more is needed than can be accomplished without changing that system. The need to address SSW gaps is pressing in the near term and the call for purposeful, prompt action by Congress, State, and Defense is clear.

This article was written by Captain Christian Haugen, USN (Ret.). Chris served as a US Navy submarine officer for 25 years retiring in 2010. From that time he has served as a leader and business development lead at well known companies within the defense industry.

In an interview with The Watch, Captain Christian Haugen, USN (Ret.), provided a perspective on the US’ continued dominance of the underwater domain and subsea and seabed warfare (SSW). Asked about its importance, Haugen stated that the underwater domain remains crucial to any maritime strategy and especially so in the Indo-Pacific region. He explained that uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUV) play an increasingly important role in a variety of missions, including intelligence gathering, minesweeping, and anti-submarine warfare. Haugen went on to say that the United States Navy has a long history of leadership in the UUV space, developing and deploying UUVs for decades, and it continues to invest heavily in this technology.

Haugen, who is now the Business Development Manager for Forcys in the United States, said, “The US Navy’s dominance is due to several factors starting with our strong alliances. The US Navy works closely with countries like Australia, Japan, and Korea. Working with well-trained and well-equipped navies in support of common security objectives is a force multiplier. This is particularly important in the Indo-Pacific region, which is the point of most friction and greatest stress on our ability to answer a near-peer competitor. Captain Haugen believes the AUKUS security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States is another significant development in the underwater domain.

Captain Haugen believes dominance of the undersea domain will be crucial to any conflict in the region. At some point, should tensions escalate, task forces and other surface vessels will have to withdraw outside the range of our adversary’s long-range anti-surface missiles. Submarines and uncrewed systems, both UUVs and seafloor networks will remain to provide indications and warnings and should it be necessary, take the fight to the enemy.

High-level guiding documents such as the CNO’s Navigation Plan (2022), the Navy’s Unmanned Campaign Plan (2021), and the Submarine Forces Commander’s Intent (2020), all emphasize the importance of SSW. Budgets and programs support the push to achieve and maintain a technological advantage over its adversaries in the UUV space. The Navy’s superiority will continue to come from investment in research and development as well as continuing to foster a close relationship with the U.S. defense industry.

Keeping the advantage is about meeting the challenge

Haugen explains. “The US Navy faces a number of challenges in the underwater space, including the development of new UUV capabilities by near-peer competitors, the challenges of processing and analyzing the massive amount of data that UUVs can generate, and the limited bandwidth that is available to UUVs.

“Our near-peer competitors are catching up quickly. The first thing to be aware of is that they continue to develop capacity through aggressive ship and submarine building programs. Next is that they continue to improve their technology. The Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan now relies heavily on uncrewed maritime vessels to meet our capacity needs. Delivering those vessels—surface or undersea—will require honing technologies to allow those systems to accomplish complex missions with high levels of autonomy.

“From engineers to operators, it’s the experts in everything from UUV design and construction to UUV deployment, operations, and maintenance that are keeping us formidable in SSW. We continue to push the limits of capability and expand mission sets for UUVs through aggressive experimentation and exercises to create new doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures.”

Uncrewed systems bring new challenges. “Data overload is a good problem to have. New underwater sensing technologies can generate massive amounts of data. Take for instance the optical payloads developed by our technology partner, Voyis. They generate three dimensional maps with incredible resolution of actionable data. But just how do you share it without recovering to the surface.” You should communicate with them. Haugen describes this challenge, “The underwater domain is limited by the acoustic communications data rates. And that same acoustic comms compromises the existence and location of the undersea system. Optical systems offer higher data rates but require very close proximity for the communicating systems. Exfiltrating data or passing mission commands is a problem that will get bigger before it gets smaller.”

It’s a question of trade-offs

“The edge processing required for autonomous systems becomes a huge issue itself. Most artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) systems require significant processing power to run. This will seriously degrade mission endurance with a knock-on effect on capability. The balancing point between processing data at the edge and exfiltrating it for real-time or near real-time use is a really tough technology question that I know the Navy is working on.”

The Importance of Trust and Autonomy

“The use of unmanned systems in the underwater domain raises a number of concerns about trust and autonomy. In the air and on land, unmanned systems have been used for a variety of missions, including ISR, ASW, and strike warfare. Lethal effectors continue to have a human in the loop.” Haugen continues, “to be successful, unmanned systems in the underwater domain will need to be able to operate more autonomously than unmanned systems in other domains. A lot of work is going into this space with AI/ML. Despite these challenges, the use of unmanned systems in the underwater domain will become increasingly important in the future. They offer a number of potential advantages, including their relatively low cost, and their now accepted suitability for the dirty, dangerous, and drudging tasks as they operate autonomously.”

Our commitment

“I’m enthusiastic about Forcys and what we can bring to support SSW. I am impressed with our technology partners and their world-leading technology in navigation and positioning systems, acoustic and optical communications, optical and laser imaging, side-scan and forward-looking sonars, intruder detection systems, UUV mission software, and environmental monitoring sensors. The ability to take that and apply it to tough military problems has been very exciting. The need for this technology in SSW is enormous. I am committed to developing teaming relationships with vehicle builders and other technology providers to help support and develop the next generation of Navy undersea warfare capability.

“There is no question. The Navy is committed to investing in UUV technology and it has the personnel and the resources to maintain its dominance. If you are like me, you’d want to give them the best possible chance. We do that with our technology offering.”

If you’d like to know more or want to contact Christian Haugen please contact us.