In an interview with The Watch, Captain Christian Haugen, USN (Ret.), provided a perspective on the US’ continued dominance of the underwater domain and subsea and seabed warfare (SSW). Asked about its importance, Haugen stated that the underwater domain remains crucial to any maritime strategy and especially so in the Indo-Pacific region. He explained that uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUV) play an increasingly important role in a variety of missions, including intelligence gathering, minesweeping, and anti-submarine warfare. Haugen went on to say that the United States Navy has a long history of leadership in the UUV space, developing and deploying UUVs for decades, and it continues to invest heavily in this technology.

Haugen, who is now the Business Development Manager for Forcys in the United States, said, “The US Navy’s dominance is due to several factors starting with our strong alliances. The US Navy works closely with countries like Australia, Japan, and Korea. Working with well-trained and well-equipped navies in support of common security objectives is a force multiplier. This is particularly important in the Indo-Pacific region, which is the point of most friction and greatest stress on our ability to answer a near-peer competitor. Captain Haugen believes the AUKUS security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States is another significant development in the underwater domain.

Captain Haugen believes dominance of the undersea domain will be crucial to any conflict in the region. At some point, should tensions escalate, task forces and other surface vessels will have to withdraw outside the range of our adversary’s long-range anti-surface missiles. Submarines and uncrewed systems, both UUVs and seafloor networks will remain to provide indications and warnings and should it be necessary, take the fight to the enemy.

High-level guiding documents such as the CNO’s Navigation Plan (2022), the Navy’s Unmanned Campaign Plan (2021), and the Submarine Forces Commander’s Intent (2020), all emphasize the importance of SSW. Budgets and programs support the push to achieve and maintain a technological advantage over its adversaries in the UUV space. The Navy’s superiority will continue to come from investment in research and development as well as continuing to foster a close relationship with the U.S. defense industry.

Keeping the advantage is about meeting the challenge

Haugen explains. “The US Navy faces a number of challenges in the underwater space, including the development of new UUV capabilities by near-peer competitors, the challenges of processing and analyzing the massive amount of data that UUVs can generate, and the limited bandwidth that is available to UUVs.

“Our near-peer competitors are catching up quickly. The first thing to be aware of is that they continue to develop capacity through aggressive ship and submarine building programs. Next is that they continue to improve their technology. The Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan now relies heavily on uncrewed maritime vessels to meet our capacity needs. Delivering those vessels—surface or undersea—will require honing technologies to allow those systems to accomplish complex missions with high levels of autonomy.

“From engineers to operators, it’s the experts in everything from UUV design and construction to UUV deployment, operations, and maintenance that are keeping us formidable in SSW. We continue to push the limits of capability and expand mission sets for UUVs through aggressive experimentation and exercises to create new doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures.”

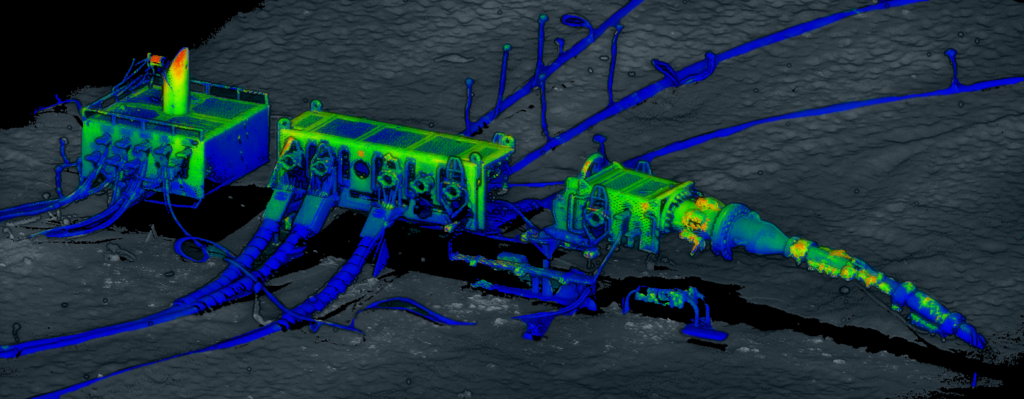

Uncrewed systems bring new challenges. “Data overload is a good problem to have. New underwater sensing technologies can generate massive amounts of data. Take for instance the optical payloads developed by our technology partner, Voyis. They generate three dimensional maps with incredible resolution of actionable data. But just how do you share it without recovering to the surface.” You should communicate with them. Haugen describes this challenge, “The underwater domain is limited by the acoustic communications data rates. And that same acoustic comms compromises the existence and location of the undersea system. Optical systems offer higher data rates but require very close proximity for the communicating systems. Exfiltrating data or passing mission commands is a problem that will get bigger before it gets smaller.”

It’s a question of trade-offs

“The edge processing required for autonomous systems becomes a huge issue itself. Most artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) systems require significant processing power to run. This will seriously degrade mission endurance with a knock-on effect on capability. The balancing point between processing data at the edge and exfiltrating it for real-time or near real-time use is a really tough technology question that I know the Navy is working on.”

The Importance of Trust and Autonomy

“The use of unmanned systems in the underwater domain raises a number of concerns about trust and autonomy. In the air and on land, unmanned systems have been used for a variety of missions, including ISR, ASW, and strike warfare. Lethal effectors continue to have a human in the loop.” Haugen continues, “to be successful, unmanned systems in the underwater domain will need to be able to operate more autonomously than unmanned systems in other domains. A lot of work is going into this space with AI/ML. Despite these challenges, the use of unmanned systems in the underwater domain will become increasingly important in the future. They offer a number of potential advantages, including their relatively low cost, and their now accepted suitability for the dirty, dangerous, and drudging tasks as they operate autonomously.”

Our commitment

“I’m enthusiastic about Forcys and what we can bring to support SSW. I am impressed with our technology partners and their world-leading technology in navigation and positioning systems, acoustic and optical communications, optical and laser imaging, side-scan and forward-looking sonars, intruder detection systems, UUV mission software, and environmental monitoring sensors. The ability to take that and apply it to tough military problems has been very exciting. The need for this technology in SSW is enormous. I am committed to developing teaming relationships with vehicle builders and other technology providers to help support and develop the next generation of Navy undersea warfare capability.

“There is no question. The Navy is committed to investing in UUV technology and it has the personnel and the resources to maintain its dominance. If you are like me, you’d want to give them the best possible chance. We do that with our technology offering.”

If you’d like to know more or want to contact Christian Haugen please contact us.

The Watch interviewed CMDR Sean Leydon (retired), Regional Manager at Forcys Australia, on the subject of the latest ADF Defence Strategy Review (DSR). The DSR sets out the Australian Government’s strategic direction for defence over the next decade.

Leydon clearly understands the significance of the DSR: “It is clear that the Government is committed to investing in new and innovative technologies, and that the maritime domain will be a key focus of this investment. There are a number of reasons for this. First, the Indo-Pacific maritime domain is becoming increasingly contested, and there is a growing risk of conflict. Second, the maritime domain is critical to Australia’s economic security. Australia is a major exporter of resources, and the maritime domain is essential for the safe and efficient movement of these resources.”

The DSR identifies a number of key areas where Australia needs to invest in order to strengthen its maritime capabilities. These include:

- Uncrewed systems: These have the potential to revolutionize maritime warfare. They can be used for a variety of tasks, including surveillance, reconnaissance, and strike. Australia is investing in the development and procurement of uncrewed systems in order to stay ahead of its adversaries.

- Artificial intelligence: Another key technology that will have a major impact on maritime warfare. AI can be used to improve the performance of uncrewed systems, as well as to develop new capabilities such as autonomous decision-making.

According to Leydon: “The investments that are made in the coming years will have a major impact on Australia’s ability to protect its interests in the maritime domain.”

AUKUS and Pillar 2

AUKUS is a new trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It was announced in September 2021, and its primary goal is to strengthen the three countries’ ability to operate in the Indo-Pacific region. Pillar 2 of AUKUS is focused on key capabilities including undersea warfare. It will involve the three countries working together to develop new and innovative technologies, such as autonomous underwater vehicles. These technologies will be used to improve the three countries’ ability to detect, track, and defeat submarines.

Leydon understands that the importance of undersea warfare cannot be overstated. According to him: ”Submarines are a major threat to surface ships and aircraft. They are also a key asset for countries that are seeking to project power in the maritime domain. The development of new and innovative technologies is essential for maintaining a strong undersea warfare capability and integral to the DSR. AUKUS Pillar 2 will help the three countries to do just that. Under AUKUS Pillar 2 the Undersea Robotics Autonomous Systems (AURAS) project, will pave the way for underwater networks consisting of crewed and uncrewed vessels, or also a networked underwater range enabling the navy to share information and coordinate actions between their vessels. This would allow the Navy to operate more effectively and efficiently and would give it a significant advantage over adversaries.

Leydon continues: ”As you know, uncrewed systems are playing an increasingly important role in maritime warfare. They can be used for a variety of tasks, including surveillance, reconnaissance, and strike. As the maritime domain becomes increasingly contested, uncrewed systems will become even more important. Why is that? Consider this:

- They are less expensive to operate.

- They are less vulnerable to attack.

- They can operate in more dangerous environments.

However, uncrewed systems are not a replacement for crewed systems, they play a complementary role. By working together, crewed and uncrewed systems can provide a more comprehensive and effective maritime warfare capability.”

While the uncrewed systems are attracting a lot of attention, the payloads cannot be underestimated. Leydon explains: “The sensors and effectors provide the capability, the platform delivers it. It’s as simple as that.”

“Obviously, it’s important that the design of the platform meets the overall purpose of the capability, that it’s fit for its purpose, such as a frigate for a medium sized, smaller armed, fast platform compared with a larger destroyer designed for a greater armament.

The same goes for an AUV – it’s important that the payload is not only high quality (such as a multi-Aperture sonar, high quality camera or laser), but its navigation, communications and tracking systems are also high quality and precise allowing it to go where it’s supposed to and find its way back. Ideally, you want both the sensors and platforms to be built using modular designs – this allows for smoother integration of the sensors and makes future upgrades more feasible.

In other cases, a designed platform isn’t even needed. For example, the dropping or strategic placement of underwater sensors will provide you with an acoustic range that can detect an adversary’s AUV, submarine or underwater vehicle.”

Joining Forcys

Sean recently joined Forcys and is spearheading our Australian efforts, “I think Australia and its UK and US partners have a lot to gain from AUKUS and the technological transfer of capabilities that already exist. The DSR specifically speaks about the Pillar 2 ‘Trilateral delivery’ or joint R&D of enhanced capabilities, this collaboration with companies like Forcys will help provide the ability for all three nations to move forward with information sharing and technology cooperation. I’m especially excited about the opportunities for Forcys with AUKUS Pillar 2 undersea warfare – from the underwater acoustic communication network in Smart Sound Plymouth from our Technology Partners Sonardyne, the world leading intruder detection sonars from Wavefront already deployed with navies around the globe and to our AUV payloads. These are just some of the amazing proven capabilities that Forcys offer.”

Want to find out more or speak to Sean Leydon? Please get in touch.

The Watch recently discussed the Royal Navy’s littoral strike capability with Justin Hains MBE, a former Royal Navy officer and current Business Development Manager for Forcys. The Royal Navy has a significant capability to strike land targets thanks to its two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, which are together capable of carrying up to 80 aircraft, including F-35B Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters. The carriers are also supported by a range of other vessels, including destroyers, frigates, logistic support ships and submarines.

Hains believes that the Royal Navy has an advanced littoral strike capability. He said: “You need to understand that the capability is absolutely there. The core of power projection is the two carriers and then everything builds from them. There’s a submarine capability to defend the carrier, and there’s a hydrographic and mine countermeasures capability to enable the carrier freedom of navigation so that the carriers can get to where they need to operate. The escorts provide a defensive screen and an ability to distribute the force in smaller packages as required. This capability has been many years in the planning and recent geopolitical events, if anything, further validate the Royal Navy’s approach”.

In addition to the Queen Elizabeth-class carriers, the Royal Navy is also investing in a range of other capabilities that will support littoral strike operations. These include:

- The Type 26 frigate, which will be equipped with a range of anti-ship and land-attack missiles.

- The Type 31 frigate, which will be a smaller, more affordable frigate that will be well-suited to littoral operations.

- The Littoral Response Group, which will provide an amphibious option, either in concert with Carrier Strike or separately.

Innovation where it is needed

Hains points out: “These strategic decisions ensure that the Royal Navy has a strong littoral strike capability for many years to come. However, the renewed threat of near-peer adversaries is more real than ever before. To meet this challenge, the Royal Navy is going to need to adapt its capabilities and strategies. The focus on littoral strike is a big step in the right direction. The navy now needs to invest in new technologies to complement its existing assets. Investment in uncrewed systems increases our surveillance range and improves our strike capability. Techniques like machine learning (ML) will be used to automate tasks and make decisions in real time.” But it’s not just technology. “In addition to investing in new technologies, the Royal Navy will also need to adapt its operational concepts. The navy will need to be able to operate more flexibly and at higher tempo. It will need to adapt to the foe and generate a response by selecting the right mix. At times the navy will operate in smaller, more distributed units. At times it will resort to conventional weaponry. At all times the Royal Navy will need to work closer with its allies and partners”.

According to Hains, if navies are going to defeat the emergent threats, then they need to be successful in fielding new technologies: “We need to deliver innovative solutions to put in front of the navy in a very rapid way. If you ask me, I think we’re getting there but to be honest the procurement process is still playing catch-up. Many initiatives are supporting rapid innovation and encouraging war fighters to be involved in their development from early stages. At Forcys, we are clutched into all of that, and we are part of the ongoing discussion. However, we recognise that defence as a whole will always have a problem with annualised budgets. These make it very difficult to launch multi-year projects. I know this is being worked on. And I accept that the commercial teams in front line commands can only change as fast as the next level allows them, but we need to feed back to defence to help them be as flexible in procuring innovation as they are when it comes to field it. You are going to see industry and defence working together and needing to be ready to take calculated risks.”

Dominance in the underwater domain will be critical to enable the littoral strike capability. As Hains explains: “It all comes down to the use of use of asymmetric force. You’re trying to get the most effect for the least resource you apply your strengths against your enemy’s weaknesses. In the underwater domain this arms race is taking place against a backdrop where the sensors and effectors are going to be required to operate at far higher speed and more integrated than ever before. It’s not going to be good enough to take a position, course and a speed from one sensor and plug those numbers into a weapon to then release it. All of this information has to be exchanged electronically and very quickly, because underwater vehicles, especially weapon systems, are going to get faster; so response times are going to have come down.”

The Importance of Underwater Networks

As Hains noted in the interview, an effective underwater network is essential for the Royal Navy to be able to conduct littoral strike operations. “An underwater network would allow the navy to share information and coordinate actions between its unmanned systems and manned ships. This would allow the navy to operate more effectively and efficiently and would give it a significant advantage over its adversaries.”

One year on

It’s been one year since Hains joined the Forcys project, he was here while the launch was being planned and participated on the launch in UDT 2022 in Rotterdam. How has it been? “I’m still absolutely thrilled to be part of something that feels really fresh, really exciting, and exactly what defence is looking for. It also feels good now that we’re getting more people in, and our expansion into the US and Australia is absolutely essential as we look towards AUKUS and other opportunities. I think there are so many synergies wrapped around AUKUS that we’re absolutely in the right place for it. I really feel like we’ve got the right model and the right recipe for success at just the right time. Especially when AUKUS rightly spins off underwater networks, defensive capabilities, and mine countermeasures capability to support anti-submarine warfare across shallow waters and confined spaces. I’m still amazed by the positive reaction I get from everyone when I explain why we created Forcys and what Forcys can offer. And I think if anything, we just need to go faster. That ability to really operate as that single point of contact will help us to accelerate again in terms of what we’re actually able to take on.”

Want to dominate the deep? Get in touch with our team.

(Featured Image of HMS Queen Elizabeth in Gibraltar by David Jenkins – InfoGibraltar under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.)

If you have to operate side-scan sonars and synthetic aperture sonars (SAS) in very shallow waters (VSW) or shallow waters (SW), the acoustic environment is particularly hostile. Higher order multi-path reverberation, unstable velocity of sound profiles, often unknown, as well as significant bathymetry, baseline decorrelation effects and generally far fewer stable platforms, all add up. The result is far less reliable end sonar products with greater impact to longer range systems. This is particularly acute in tidal and riverine environments. What to do?

Go back to the drawing board

When Solstice was developed in 2010, our technology partner Wavefront Systems decided it was time for a step up in the performance of traditional side-scan sonars. The aim was to deliver a high-frequency, high-resolution, and long-range sonar that would provide a marked improvement in the probability of detection of mine-like objects while minimising the probability of false alarms.

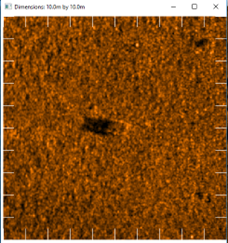

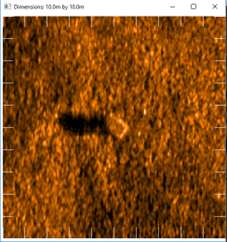

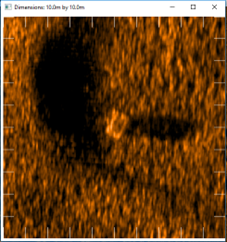

Solstice was designed to do just that. Step one was to design a multi-aperture array which would improve the signal-to-noise ratio extending the range over other sonars operating at the same frequency. However, longer ranges in shallow waters are susceptible to multi-path reverberation. Dr Rob Crook, Research Director at Wavefront Systems explains how Solstice overcomes this problem: “The dominant source of noise for all side-scan sonars operating in shallow waters is ‘multi-path’ reverberation. The nature of this noise means many acoustic pathways scattering from spatially unrelated regions of the underwater scene may none-the-less return to the sensor with identical flight-times. The inability of any ‘2D’ (range, bearing) sensor to discriminate between these contemporaneous pathways leads to an inevitable loss of contrast. Multi-path Suppression Array Technology (MSAT) is a physical array-based technology that offers the swathe coverage one would traditionally have associated with wide elevation beam-widths, with the shadow contrast associated with very narrow beams. MSAT allows high shadow contrast right out to the maximum range of the sensor whilst maintaining high quality imagery close to nadir.” Why is contrast important? It helps to differentiate targets from the surroundings.

In addition, Solstice implements dynamic focusing ensuring that the image will maintain the highest possible resolution at the position in space relative to the sensor, meaning that the resolution will improve as the range to the target decreases. While at longer ranges the interpolated real-time imagery drastically aids human visual perception.

What does it all mean?

The design choices lead to significant advantages for Solstice users. These are some examples of where Solstice excels.

- Simpler to operate: Solstice is simple, the area coverage rate increases with speed while the range remains constant. This makes mission planning easy. You can understand and use the constant range to plot a survey route and you can observe the area that is under consideration. The survey outcome becomes more predictable and simpler to manage.

- More robust: Systems like SAS are known to be very sensitive when mounted on an unstable platform or operating over complex seafloor environments. Any dynamic changes may impact the quality of the SAS data; mud sediments can result in complete loss of micro-navigation data, and in the worst outcome the SAS needs to revert to normal side-scan mode. SAS typically operates at a lower frequencies hence this corrupted SAS side-scan data is not suitable for most operations. Solstice MAS does not share this problem.

- High currents: In MAS the range is limited as a function of the so-called ‘crabbing angle’ but the image quality is preserved along the whole swath.

- Shallow waters: Operations in confined spaces and shallow waters (20m to 30 m depth) are difficult for SAS systems or lower frequency side-scans. These systems can become range limited as the multipath effects from surface returns has an impact on the SNR performance and this is common for all side-scan sonars. For some SAS systems, these effects can compromise as much as 50% of their swath but with Solstice MAS, the impact will typically be less than 10%.

|  |  |  |

| 22 m | 47 m | 72 m | 92 m |

Please contact us to find out more.

Leading navies are focused on technological innovation, but it is time to outpace the rate of technological change. It is time to go further than partnerships. In this article Ioseba Tena, Commercial Director at Forcys, challenges navies to go further than ever before.

In the past, the introduction of new naval technologies has been driven and dictated by navies themselves according to changing mission requirements and their understanding of the technology available. But within the evolving threat landscape, navies are starting to embrace the incessant pace of technological change by sharing more with industry. This sharing is essential if you need to develop and leverage new technologies to address present and future threats.

Evolving threats

Threats are swiftly evolving, unpredictable and varied. Traditionally, drones were largely confined to the aerial domain. Now, unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) threats are evolving rapidly. You must quickly develop and integrate the technologies and expertise to protect crews, vessels and critical infrastructure.

The common causes of protecting people from attack and the environment from disaster unite academics and navies. While there is some collaboration, the two communities often operate separately. Academia can be tasked to drive focused innovation, but these institutions are neither motivated nor incentivised to fund the production of fully formed security solutions. That means involving defence suppliers at the earliest possible stage in concept discussions. The best innovation will come from a well-grounded understanding of the size and scale of the challenges. Project risk, which invariably manifests itself as increased costs and time, could be reduced by inviting industry to embark in vessels to see the operational challenges first hand (a way perhaps to break the old cliché of waiting too long and then not getting what you actually needed!)

In the underwater domain, identifying, classifying and neutralising threats poses numerous challenges, largely because contacts underwater are notoriously difficult to evaluate. Intruder detection is difficult due to poor visibility, variable terrain, noise and the presence of other objects in the water such as marine life or debris. It’s no longer just large, manned, submarine platforms either; the threat could come from combat divers who are small and very quiet, or UUVs which are faster and therefore difficult to track.

Partnerships

It’s for this reason that naval forces cannot be islands. To gain a battle-winning advantage and neutralise threats, whether from the air or the sea, collaboration across industry, government enterprise and academia is a recognised necessity. Together we need to work towards a capability ecosystem that supports and promotes the swift and successful development of new technologies, enabling us to stay ahead of emerging threats and maintain operational advantage. This ecosystem goes beyond a narrowly-defined partnership. Industry, academia and navies must learn to communicate, innovate and learn from each other in order to ensure that forces on the front line have the necessary capabilities to carry out safe, successful operations.

Did you know that Forcys is the result of partnership between leading instrument vendors in the underwater domain? That’s why we understand that the ecosystem described above is key to the success of technology innovation. Our technology partners already have a strong legacy of working with industry, academia and government organisations. We continue to proactively look to forge relationships with academia to deliver the solutions to meet your needs, on time and on budget. Forcys and our technology partners can leverage university resources and insights to inform the next generation of technology, products and services for its customers.

For example, our technology partner Sonardyne is currently collaborating with Newcastle University on a new open standard in underwater communications. The standard, named Phorcys and funded by the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, is a high-integrity secure waveform for underwater acoustic communications. Another good example is the collaboration between our technology partner Voyis and McGill University. They are producing a new generation of optical processing techniques for illuminating the underwater domain. Both projects have been primed with knowledge and experience from the commercial sector. The latest step is applying the technology to naval applications. At which point you will be able to find off-the-shelf technologies that meet naval capability requirements.

Government agencies and navies are increasingly recognising the importance of secure, open standards to begin using commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) components. As you know it’s critical to minimise project risk. How? By applying extensive knowledge and expertise in underwater communication and location technologies. Our technology partners have been at the heart of no-fail delivery for commercial customers for over 50 years. This means we have the expertise to deliver allied forces the interoperability needed to conduct successful operations at home and overseas.

At Forcys we are interested in talking to anyone who would like to be part of an ecosystem driving naval technology innovation. We want to create the best defence systems in the world. Invite us to see the problem and discuss your needs.

Please contact us to find out more.